Beyond Dopamine: Building a Healthy Recovery Pyramid for Your Nervous System

My mum had a simple standard for a good meal: "all the colours." For her that meant some meat and at least three different vegetables. I never asked her where the rule came from. I don't remember the healthy eating pyramid being launched in Australia, but "all the colours" is a neat way to summarise it; a quick reminder that nutrition isn't about obsessing over single nutrients, but about variety, balance, and hitting the fundamentals.

We need the same approach to managing stress.

What the Dopamine Conversation Misses

There's been a lot of buzz lately about "dopamine detoxes,” the idea that we can reset our brains by abstaining from scrolling, gaming, and other quick hits of stimulation. Recently, clinical psychologist Anastasia Hronis wrote in The Conversation that attempting to completely detox from dopamine is impossible, since dopamine is essential to human functioning, involved in everything from reward and motivation to movement, arousal and sleep. She also notes that a 24-hour abstinence period won't produce lasting changes: research shows that "after the period of abstinence, old habits and urges often return, unless people actively build new routines and coping strategies."[1]

Buried in this reality check is also an insight that deserves much more attention.

Hronis advocates for replacing "fast dopamine" with "slow dopamine" activities. This distinction is the real game-changer. Fast dopamine comes from scrolling, video games, sugary snacks, and online shopping: quick, intense bursts that feel rewarding but create a cycle of escalating stimulation-seeking. Slow dopamine emerges from activities that may require a little more patience and sustained effort: creative projects, exercise, learning something new, face-to-face connection, or listening to music you genuinely love.

All true, but here’s what the narrow focus on dopamine risks missing: the real magic of slow dopamine activities isn't just that they feel good. It's that they fundamentally shift your nervous system into a different operating mode.

Your Nervous System Has Two Modes

Your autonomic nervous system operates through two complementary branches: the sympathetic nervous system (your accelerator: fight-or-flight, “go” mode) and the parasympathetic nervous system (your brake: rest-and-digest, “slow” mode).

Most of us spend our days in sympathetic overdrive. Work deadlines, notification pings, email apnea, status comparison via socials, and so on through a seemingly endless 21st century list, mean that our stress response is constantly activated. Over time, this is what leads to burnout: exhaustion, cynicism, going through the motions, and that numb, blank feeling of running on empty.

The antidote isn't just "doing less." It's actively engaging your parasympathetic nervous system, which runs on a neurochemical cocktail that's much richer than the dopamine fixation might lead you to imagine. This is where acetylcholine, oxytocin, vasopressin, and prolactin come in, for example, hormones that orchestrate your body's rest and recovery.

When you activate your parasympathetic system, your body does the things it needs to do to recover: it inhibits adrenaline and slows your heart rate, it digests food properly, it consolidates memories, it regulates inflammation. It's not a luxury. It's how your body actually heals.

And here's the practical part: "slow dopamine" activities reliably engage your parasympathetic system. Research shows that social connection and conversation are associated with oxytocin release, which supports calm and bonding.[2] Similarly, focused creative or learning activities stimulate acetylcholine production, a neurotransmitter linked to attention, memory, and the relaxation response.[3] Gentle exercise, time in nature, and music all engage parasympathetic pathways through multiple neurochemical mechanisms.[4] They don’t just feel good, they're physiologically restorative.

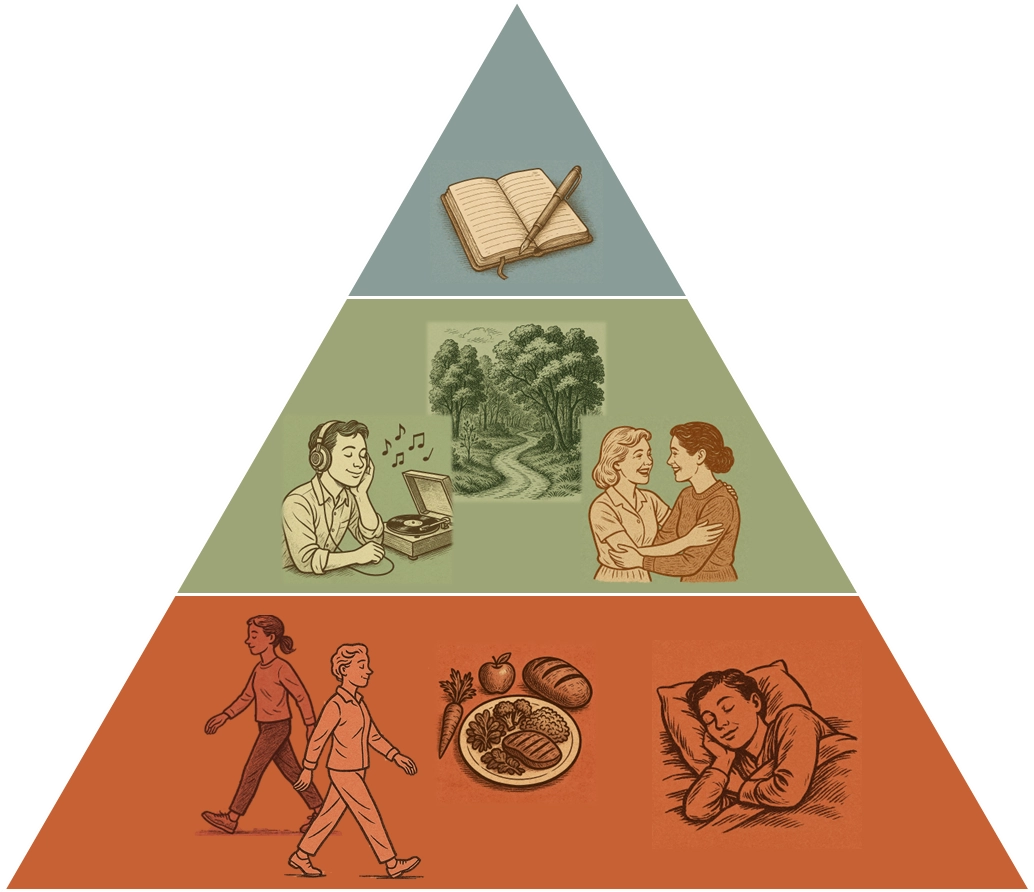

A Healthy Recovery Pyramid for Your Nervous System

Rather than treating recovery like a to-do list, another thing to optimize or perhaps feel guilty about, it helps to think of it as a range of options to choose from, like we do with nutrition.

The Foundation: Physical Health This is your daily mental health leg-up. Good sleep, regular gentle movement, and nourishing food create the baseline conditions for a less reactive stress response and easier parasympathetic activation. Sleep deprivation, sedentary work days, and running on processed food and caffeine will make everything else harder. This layer isn't glamorous, but it's load-bearing.

The Middle Layer: Connection and Engagement Building on the base layer, this where the restorative magic happens. Connecting with people you care about (face-to-face when possible), engaging with your values through meaningful work or hobbies, time in nature, creative pursuits, learning something new: these activities are relaxing, playful, absorbing, and they activate multiple parasympathetic pathways simultaneously.

The Top Layer: Reflection and Integration Regular practices like meditation, journaling, prayer, or simply sitting with your thoughts help you process the chaos and consolidate what’s working for you. This layer integrates and amplifies the benefits of the layers below.

All the Colours

The research on stress recovery suggests that variety in recovery activities may matter more than frequency. That said, you need reasonable frequency to achieve meaningful variety. The point isn't to do everything, it's to make sure you're hitting all the layers.

Pick one or two things from each layer that genuinely appeal to you. Make the best ones easy to access. And remember, the goal isn't perfection. You don’t need a detox, you just need to remember: include all the colours.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is this the same as a "dopamine menu"?

Not quite. The dopamine menu is a useful tool if it helps you to identify reliable mood-boosters and makes them easily accessible. But by framing everything around dopamine, it misses the bigger picture. The recovery pyramid goes further: it helps you understand why certain activities work (because they activate parasympathetic recovery pathways), helps you commit to activities that might take a bit more effort, and structures recovery into connected layers rather than just a flat menu.

Q: Do I really need to do all three layers?

Yes, they're interconnected. It’s much harder to engage fully in any of the other activities if you're sleep-deprived. Connection and engagement are where the real restorative magic happens. Reflection helps integrate everything so that it actually sticks. And done consistently, the top two layers make sleep, movement and healthy eating easier too. Remember, you don't need to do everything in every layer, just make sure you're hitting all three categories regularly.

Q: How often do I need to do these activities?

Research on stress recovery suggests that variety may matter more than frequency, but you need reasonable frequency to achieve variety. Consider the base layer a daily commitment, and expect to spend most of your recovery time there: sleep, gentle movement, and healthy food are daily priorities, but ones to enjoy, not dread. If you’re finding any of them tough, look for what’s getting in your way, and start with whatever you have some control over. You don't need to solve everything at once. The middle layer might only be once or twice a week: half an hour catching up with a friend or losing yourself in a creative project will have recovery value in its own right, and may also help you to get moving and improve your sleep. On the top layer, even 5-10 minutes of reflective practice a few times a week can have measurable health impacts.

Q: What if I don't have time for all this?

This is the most common objection, and it's usually the sign that you need it most. Start small. Pick one thing from each layer that genuinely appeals to you (not what you think you "should" do). Make it ridiculously easy to do. A 10-minute walk in a green space hits the foundation + middle layers. A coffee and catch-up with a friend hits the middle + top layers if it helps you connect and process. Five minutes of journaling before bed will improve your sleep. You're not aiming for a total overhaul, just a few adjustments that create consistency and variety.

Q: Will this actually help with burnout?

Burnout is fundamentally about chronic stress without adequate recovery. By systematically engaging your parasympathetic system through all three layers, you're directly addressing the root cause. Research on recovery and wellbeing shows that varied, regular engagement with restorative activities significantly reduces burnout symptoms over time.[5] But it does take consistency; this isn't a 24-hour fix, detox-style.

Q: Is meditation enough to prevent burnout?

It depends what kind of meditation, and how long you’re practising for, but probably not. Different practices are valuable in different ways, for example in training attention so you can avoid dwelling on stressful events, prompting reflection, or activating the relaxation response. However, no practice is likely to provide sufficient recovery on its own. Meditation without good sleep, connection, or engaging with things you care about can become yet another task rather than genuine recovery. The pyramid framework puts it in context: recovery is multi-layered, and mindfulness can play a part. But for many people, the foundation (sleep or movement) is the missing piece. For others, it's connection or engagement.

Q: How is this different from "self-care"?

Self-care, in the commodified form that’s often marketed on social media, focuses on one-off pampering activities or products. They're often positioned as luxuries for when stress gets intense, isolating them from a normal daily or weekly routine. True self-care is rooted in nervous system science: it's about understanding how your body actually recovers, and building a sustainable system that hits all the mechanisms of physiological restoration. It's less about bubble baths and more about intentionally activating your rest-and-digest response, and then allowing it to do the job evolution trained it for: keeping you healthy and energised.

Q: Isn't "slow dopamine" just another marketing term, made for social media attention? Isn't it all just dopamine?

Fair question. While both fast and slow dopamine activities involve dopamine, they differ significantly in how they affect your nervous system. Fast dopamine activities create a rapid spike followed by a crash, which keeps you seeking the next hit. Slow dopamine activities produce more sustained, moderate dopamine release alongside activation of other neurotransmitters (oxytocin, serotonin, acetylcholine) that create a more stable emotional state. The distinction matters because it explains why some activities leave you depleted while others feel genuinely restorative. It's not the dopamine itself, it's the whole neurochemical profile.

Q: How quickly can I shift into parasympathetic mode?

It varies. Your body can begin activating parasympathetic responses within minutes. A few deep breaths, stepping outside, or starting a conversation can initiate the shift. But meaningful nervous system recalibration takes longer. A single 15-minute walk will help, but a safer bet is 30 minutes, and it's consistent engagement over weeks and months that rebuilds resources and increases resilience. Think of it like fitness: one workout helps, but the benefits compound over time.

Q: If I engage in parasympathetic activities, isn't that just procrastination?

This is a real tension, especially for the perfectionist high performer most at risk of burnout. The key difference is intentionality and integration. Procrastination is avoidance that comes with guilt and a last-minute rush, producing work you're less than proud of. Strategic recovery is intentional restoration that improves your capacity to perform. The irony is that chronic sympathetic activation (always "on," always pushing) depletes your cognitive resources, creativity, and decision-making. People who build in genuine recovery often accomplish more because they're working from a fuller tank. That said, if you’re using “recovery” activities to delay important work without a plan to address that work, you’re in a lose-lose bind where you’re neither productive nor really recovering. That's a different problem worth examining.

Q: Do these activities work equally well for everyone?

No. People with anxiety, trauma histories, or certain neurodivergent profiles may find some parasympathetic activities uncomfortable, dysregulating or just impossible. For example, meditation can be anxiety-provoking for some; sleep can be a challenge for others; social connection might feel overwhelming. The pyramid framework is flexible. You get to choose what works for your nervous system, not what you think you "should" do. Working with a therapist or counsellor can help identify which activities genuinely settle your system versus which ones crank the pressure up.

Q: How do I know if I'm really activating my parasympathetic nervous system?

Your body will tell you. After genuine parasympathetic activation, you might notice a slower heart rate, deeper breathing, relaxed shoulders, softer jaw, clearer thinking, or a sense of calm. Some people feel a subtle feeling of lightness or "release" as pressure lifts, others a heaviness in their arms and shoulders as muscles relax. Conversely, if you're forcing yourself through an activity you don't enjoy, you may feel tension or restlessness instead. Trust your body's feedback. If something feels good and leaves you feeling genuinely restored (not just distracted), you're likely on the right track. These internal sensations may take some practice to tune into, but over time, you’ll learn to recognize what works for you.

Q: What if I don't have access to face-to-face connection or nature?

Valid constraint. The pyramid is adaptable. If in-person connection isn't possible, video calls or even phone conversations with someone you trust can activate oxytocin and connection. If nature access is limited, even images of nature, plants indoors, or listening to nature sounds provide some benefit. The principle matters more than the exact activity: you're looking for things that create genuine engagement, relaxation, and a sense of meaning. For some people in urban environments with limited access, it might be creative projects, music, or community involvement instead.

Q: If I have great sleep but zero social connection, can I still recover from burnout?

That’s a harder path to travel. While good sleep is foundational and essential, burnout is multifactorial. Chronic stress depletes your sense of purpose, erodes social bonds, and makes it hard to experience positive emotions, all of which are difficult to address through sleep alone. Connection, meaning, and engagement aren't luxuries; they're core mechanisms of recovery. Someone with perfect sleep but profound isolation will likely still feel hollow and depleted. The pyramid works because all three layers matter. That said, starting with whichever layer is most broken can create momentum for the others.

Q: Isn't the foundation layer just basic health advice I already know?

Probably. Most people know sleep, movement, and nutrition matter. The issue is that under burnout conditions, these fundamentals often collapse first. Work pressure crowds out sleep. Stress kills appetite or drives comfort-eating. Energy depletion makes exercise feel impossible. Knowing it matters and actually doing it under chronic stress are different problems. If the foundation is already solid, great; you can focus on the middle layer. But for many people experiencing burnout, rebuilding the foundation is the recovery work, and it's often more impactful than adding meditation or hobbies on top of sleep deprivation and poor nutrition.

References

[1] Hronis, A. (2025). What is a 'dopamine detox'? And do I need one? The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/what-is-a-dopamine-detox-and-do-i-need-one-254813

[2] Matsushita, H., & Nishiki, T. (2025). Human social behavior and oxytocin: Molecular and neuronal mechanisms, Neuroscience, (570): 48-54.

[3] Hasselmo, M. E. (2006). The role of acetylcholine in learning and memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 16(6), 710-715. For acetylcholine's role in attention and learning: Sarter, M., Hasselmo, M. E., Bruno, J. P., & Givens, B. (2005). Unraveling the attentional functions of cortical cholinergic inputs: interactions between signal-driven and cognitive modulation of signal detection. Brain Research Reviews, 48(1), 98-111.

[4] For parasympathetic activation and recovery: Thayer, J. F., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 201-216. For multiple pathways to parasympathetic activation: Porges, S. W. (2003). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic contributions to social behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 79(3), 503-513. See also: Chanda, M. L., & Levitin, D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(4), 179-193 (on music and parasympathetic activation).

[5] Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204-221.